It’s Thanksgiving week. I’m thinking about friends and family. My dad, stepmom, her brother, his son, are coming to Chicago. It’ll be cold outside, but warm inside. Seems like an appropriate time to tell you a little bit about my dad’s dad, Geraldo Cadava Jr., after whom I’m named. Indeed, I couldn’t proceed much further with this newsletter project without telling you about him.

He has meant too much to me for you to not know something about him.I didn’t even realize it until I was in my thirties, but he has profoundly shaped my perspective on Latino history and politics; not necessarily because of anything he has done, but because of his example. To me, he represents the impossibility of precisely articulating any single meaning of what it means to be Latino.

I call him Grandpa Jerry. His old friends called him “Lándo.” My grandma—Gloria (“Glo,” or “Kiki”)—used to call him that, too. I say “called” and “used to” not because he has passed. He’s 96-years-old and living at the VA home in Tucson, Arizona. I just don’t think anyone calls him that anymore.

I had the chance a couple of years ago to share a little bit about him with the great Alissa Escarce and Maria Hinojosa, for Latino USA. Listen here: “A Third of the Latino Vote.”

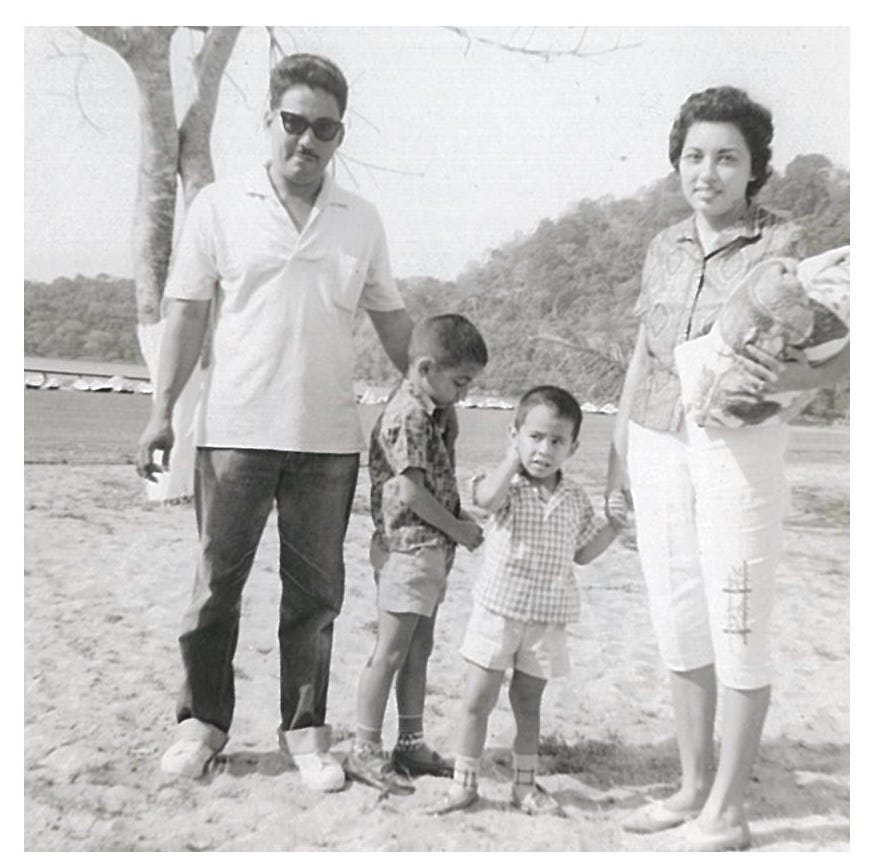

He’s half Filipino, half Colombian, and was born in Colón, Panama. Yes, the city named after Cristobal Colón—Christopher Columbus. He was born in 1926, and moved to the United States in 1943. The family settled in San Diego, where my grandpa went to Union High School and then joined the military. He married Gloria, a Mexican American woman born in Lordsburg, New Mexico, and raised in Safford and Clifton, Arizona. She was the sister of my grandpa’s friend in the Air Force. They had two kids, my dad and my Tío Pedro, Uncle Pete. My grandpa’s career in the Air Force took him back to the Panama Canal Zone, where my dad was born, and then to Texas and Tucson, where he ultimately retired at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base.

Tucson is where I was born.

My grandpa had risen to the rank of Tech Sergeant in the Air Force, and after his retirement he washed dishes at the Forty Niner Country Club and worked at the Silver Bell Copper Mine outside of Tucson. He experienced racism in the military and the mines, but that never shook his faith in the idea that the United States was a good country, where he had been able to buy a home and raise his kids. One time, he told me that in a career that lasted more than two decades, he made more than a quarter-million dollars. You do the math. Nevertheless, he was extremely proud.

He voted for a Republican for the first time in 1980, when he voted for Ronald Reagan; he was one of many Reagan Democrats. I still hear from my students about the Reagan Democrats who were Latinos; they tell me about how their grandparents were always like, Reagan this, Reagan that. As recently as a few years ago, when he still argued about politics, he told me that Donald Trump was a good guy because he’s a Republican. Period. I miss those days. We disagreed about everything when it came to politics. He had a real fighting spirit. It was aggravating then, because he never gave me an inch; barely even acknowledged my point of view. But at least he was more engaged with the world around him than he is today. I know, it’s just age.

Arguing about politics was our favorite pastime. That, and going to play catch at the nearby elementary school. I remember sitting on his bedroom floor, listening to him tell stories about his childhood best friend in Panama—Edward Bringas, after whom my father is named—and how they bought ice cream for a nickel. His other main subject was his military travels—to Alaska, Japan, all over the place. He said he once told General Curtis LeMay that he couldn’t smoke a cigarette so close to an airplane, because it might start a fire and cause the plane to explode. LeMay told him that “it wouldn’t dare.”

My grandpa interrupted these stories with pronouncements that immigrants should come to the United States legally, like he did; that the United States was a good and fair country; and, after the advent of cable news in the nineties, that Bill O’Reilly was “looking out” for him. I countered with everything I could. My grandma, whose politics aligned more with my own, told me to just ignore him.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but my arguments with him taught me important lessons. They trained me to be curious about the beliefs of other Latinos whom I didn’t necessarily agree with. This helped me immensely when I interviewed conservative Latinos for my book, The Hispanic Republican.

We locked horns all the time, but I loved him. After our arguments, he made me a fried hot dog or one of his signature bacon, pea, Swiss cheese omelets—don’t knock it if you haven’t tried it. We watched movies together, talked about cars, went for walks around the block.

Because of my experience with my grandpa, it aggravates me to this day when I hear liberal Latinos like me calling conservative Latinos sellouts, race traitors, or “pochos” who aspired to be white. These ideas don’t capture anything about my grandpa, and, if I were to ask the Latinos saying these things about their own families, I bet you many of them would have close relatives like my grandfather, about whom they could tell stories similar to the ones I’ve unfolded here. Would that mean they believe their grandparents, parents, aunts, uncles, siblings, and cousins, are also sellouts and race traitors who want to be white?

In any case, these words—I’d even call them slurs—never matched my impression of my grandpa. He was proud of his race/heritage/ethnicity, spoke Spanish his whole life, and looked forward to the evenings when he and my grandma would go to Sonora Dinamita and Sonora Ponceña concerts, to dance the night away with friends.

Three more quick observations.

My grandpa wasn’t rich. Far from it. I know that when most of us think of Latino conservatives, we think of folks like Robert Unanue, the head of Goya Foods, or Arte Moreno, the owner (for now, at least) of the Los Angeles Angels baseball team (also from Tucson, interestingly enough). That’s not my grandpa. His conservatism, more than anything else, I believe, came from his deep loyalty to the United States, as the country that gave him every opportunity and allowed him to provide for his family. I’m sure there are other reasons, too, but this is the main thing that sticks out to me.

He has lived most of his life as a Colombian-Filipino-Panameño in an area of the country—the Arizona-Sonora border region—that’s overwhelmingly associated, at least in terms of Latino history, with Mexicans and Mexican Americans. Yes, just another reminder that it’s difficult to paint Latinos in broad brush strokes. Pointillism is more appropriate.

The imperial and colonial ties that have shaped Latino history aren’t only those that bind the United States and Latin America, but also those that tie the Pacific World to the Americas. My grandpa’s dad, Gerardo Cadava, who came from Philippines in 1903, is a reminder of this.

What does all of this mean to me? When I write about Latino history and politics, I feel like I’m forever trying to explain—to myself as much as to others—Latinos like my grandpa. I’m not trying to write in generalities and I’m not trying to characterize the 50.1 percent of Latinos who support particular policies or candidates. I’m trying as best as I can to represent 100 percent of Latinos, with all of their idiosyncrasies and unrepresentativeness. It’s a luxury I have as a scholar, as compared with, say, a political consultant or pollster being paid by a campaign to get their candidate over the top. I’m not saying my position is better, but it’s different.

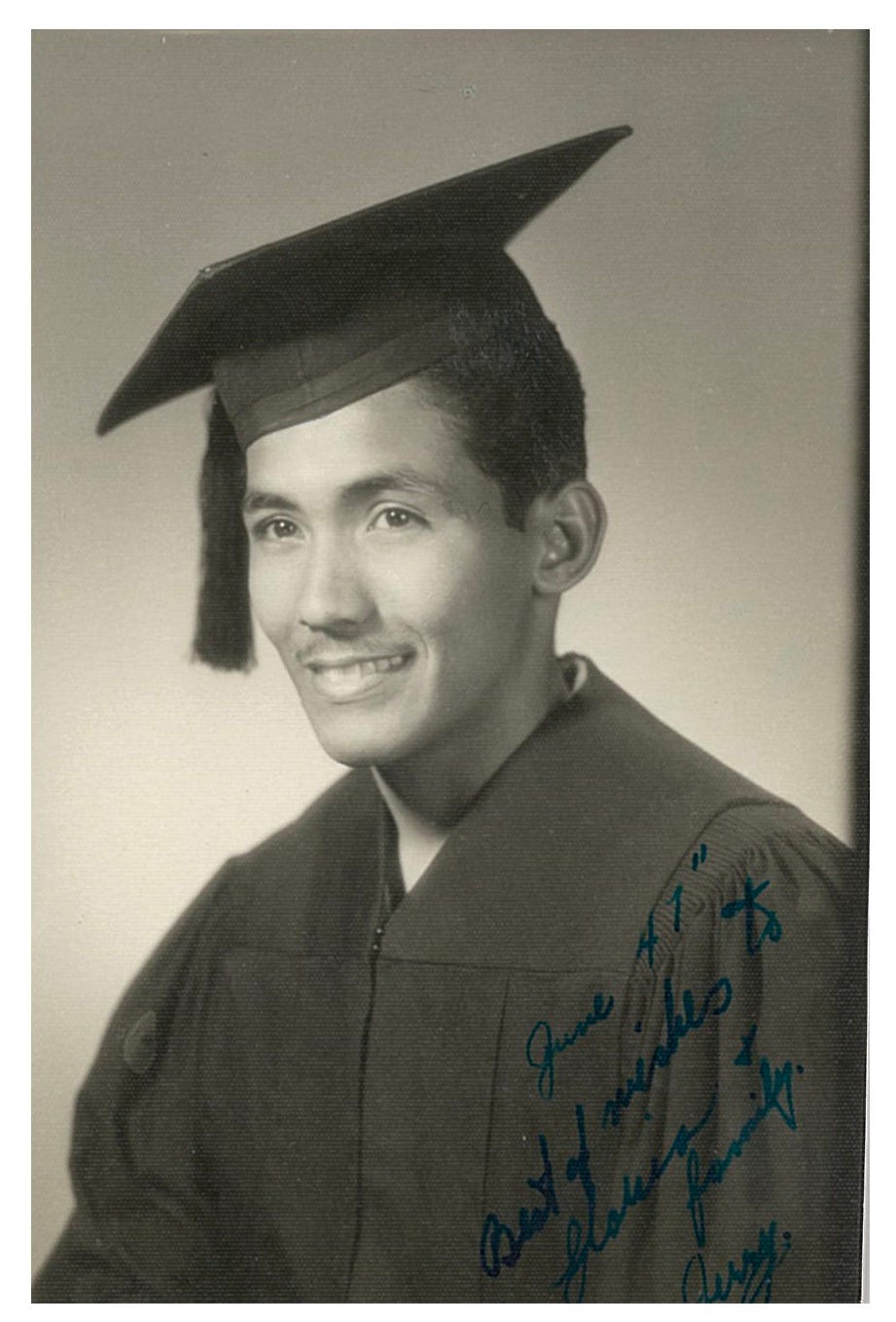

When I write, I keep two reminders of my grandpa nearby: his Panamanian passport, and his Arizona driver’s license. In case you’ve been wondering, the image affixed to several of my newsletters is a picture of the passport my grandpa carried with him as he entered the United States.

Thank you for reading, as always. I know that today I’ve asked for your indulgence, because why would you care about my grandpa? But maybe some of these stories are relatable? See you again on Thursday, and I hope your Thanksgiving prep—whatever that looks like for you—is going well.

Fascinating! What a life!

I enjoyed reading this, thank you.