The site where Pánfilo de Nárvaez, Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, and Estebánico landed in Florida

While in Tampa this week, I rented a car and drove across the bay to St. Petersburg, to visit the “Jungle Prada Site.” It’s believed to be the point where the ill-fated Pánfilo de Narváez expedition, including Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, got lost off the Florida coast, sent small boats to shore, and first encountered the Tocobaga—one of the tribes that today’s Seminoles claim as ancestors. From there, Cabeza de Vaca traveled across the continent and eventually published La Relacion de Cabeza de Vaca, the famous book some have called the first work of Latino literature.

Between 1527 and 1536, Cabeza de Vaca walked from Florida to New Mexico and then down into Mexico (none of which had these names at the time), living among several Indigenous communities, in search of a city made of gold, accompanied by a small number of other Spaniards and an enslaved African named Estebánico. By the end of his journey, in Mexico, he was unrecognizable to the Spaniards he met. He was transformed; no longer Spanish, not Indigenous, but something else. What’s more Latino than that?

Cabeza de Vaca returned to Spain in 1537, and his narrative was published there in 1542. The best book about Cabeza de Vaca is Andres Reséndez’s A Land So Strange: The Epic Journey of Cabeza de Vaca.

Google Maps told me I was getting close. I looked out the car window, saw a Wendy’s, and chuckled at the thought of hapless Spaniards stopping by for lunch.

The property is currently owned by the Anderson family of St. Petersburg. David Anderson, whose grandfather purchased it, is proud that his tour of the site, according to Trip Advisor, is ranked thirteen among historical tours in the United States. Only a tour of St. Augustine ranks higher in Florida. His family introduced peacocks to the property. Now there are more than fifty of them, many perched high in the tree tops. Is there anyone else out there who didn’t know that peacocks could fly? He told me it was a really fun place to play hide and seek as a kid.

There were at least three archaeological digs there in the twentieth century. Through carbon dating, he has learned that the Tocobaga were most active at the site between 1480 and 1550, which includes the year when Narváez, Cabeza de Vaca, Estebánico, and others were there. There are several Indian mounds, around which have been found shards of pottery and various Spanish objects. The shells in these pictures have been there for at least five hundred years. They’ve been moved around by the winds a little bit, Dave told me, but have largely sat undisturbed. The Tocobaga ate the critters inside, then used the shells as cups for their “black drink”—a tea they made from yaupon holly, or “ilex vomitoria,” which got its name because they drank it until they vomited as a form of expurgation. Below is a picture of a yaupon holly bush that is just beginning to grow leaves again after getting damaged by Hurricane Helene, and of a pile of shells that were at once food and cup.

We walked in a large circle around the property, as Dave told stories about his family’s history at the site, taught me about the work of local historian James E. MacDougald, who is deeply invested in proving that this is the exact spot where the Spaniards landed, and showed me drawings of what the Tocobaga village, where the home he grew up in is now located, is believed to have looked like. Here’s Dave.

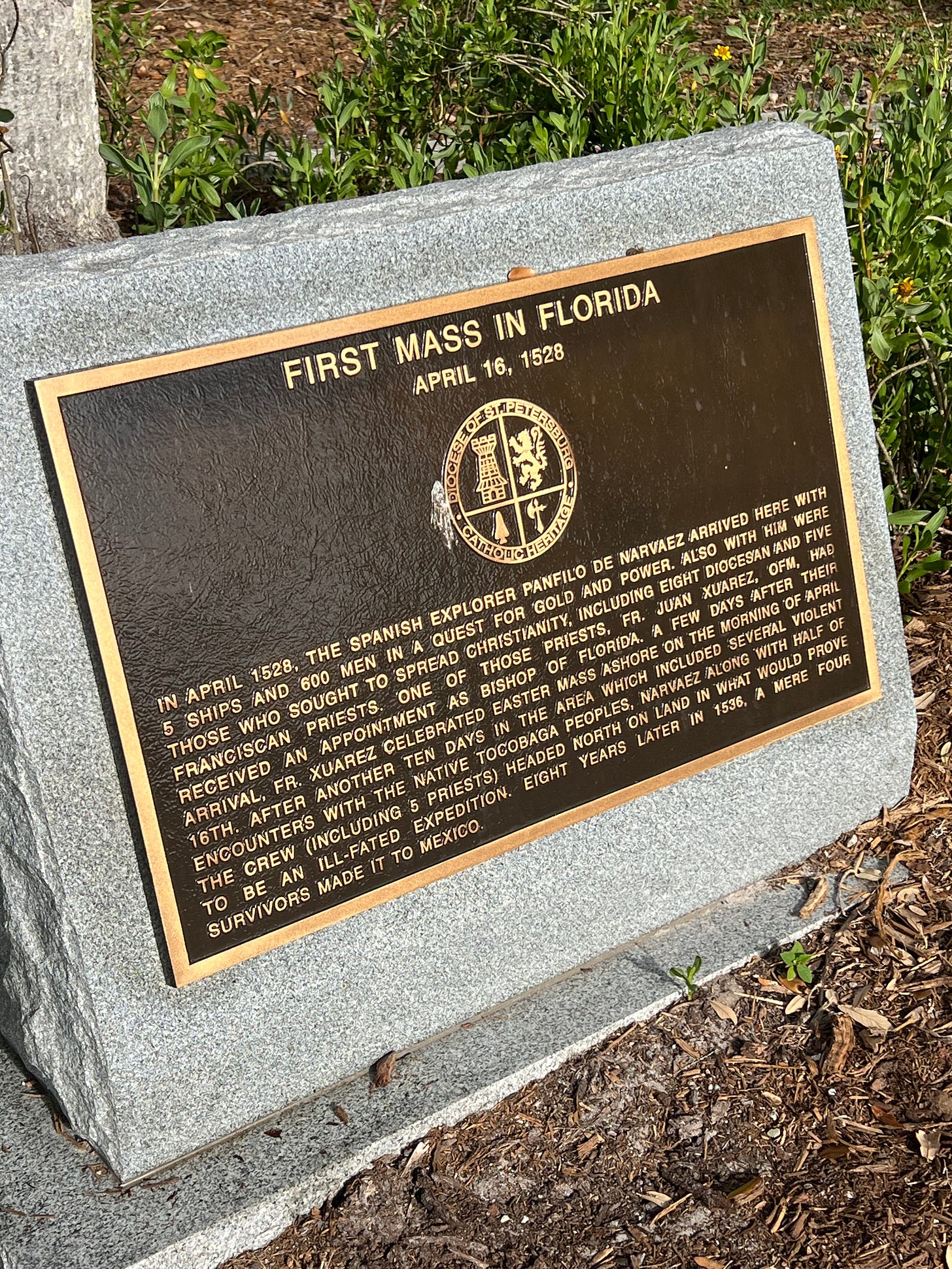

Not even a hundred feet north of the property is a historical marker at the site of the first Catholic mass held in Florida, on April 16, 1528.

Just to the south and the west are the beautiful and relatively shallow Boca Ciego Bay and the barrier reefs that the Spaniards had to cross in small boats in order to reach the mainland.

After twenty years of reading and assigning Cabeza de Vaca’s narrative, it was awesome to set sight on the place where his journey began. It’s one thing to read about it and take studious notes on the details of the text, and quite another to breathe in the air, look at the water, and stare across the bay at the barrier reef—changed as they are—where an incredibly important episode of Latino and American history took place.