The Aztecs

A new history by Camilla Townsend and what it means for Mexican American (and Latino) identity

Camilla Townsend is a historian at Rutgers University and the author of a new-ish book about the Aztecs, titled Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs, published by Oxford University Press in 2019. It has already received prestigious awards such as the 2020 Cundill History Prize. I’m a little late to the party. But I recently read Fifth Sun for two reasons. First, because I’m writing a book about Latino history over the past 500 years and more, which I plan to begin with chapters about mesoamerica and the Spanish colonial period. Second, I read it because Townsend is giving a talk at Northwestern today, and I’m excited to meet her!

What’s “new” about Townsend’s interpretation? First, it’s based on Nahuatl-language accounts of the conquest in addition to the histories written by Spaniards in Spanish. Second, it covers the periods before, during, and after the conquest, offering a narrative of survival and not only of destruction. From my perspective, though, it’s also new because it contains important lessons—correctives, really—for my field of Latino history.

Let me be clear: Townsend is not a Latino historian, and her book is not Latino history, per se. Yet what she has to say about the Aztecs has important consequences for Mexican American history in particular, but also Latino history overall. It revises the stories we’ve told about Mexican American origins, and should reshape how we think and talk about Mexican American and Latino history going forward.

Some of Townsend’s colleagues in the field of colonial Latin American history have denied that the colonial period should even be considered part of Latino history. It’s just too far back in the past, and bears little relation to Latino history today; it’s a foreign world. Yet despite such quibbling, Latinos for more than a century have continued to think of the Spanish colonial period as their origin story. As long as this remains true, Latino historians need to be in conversation with, get up to speed with, and ponder how stories about the colonial period make their way into the histories we write about Latinos in later eras.

Latino history as many conceive of it today—the conglomeration of people from different national backgrounds, such as Mexican Americans, Cuban Americans, Puerto Ricans, Dominican Americans, Colombian Americans, Venezuelan Americans, Puerto Ricans, Central Americans, and etc—couldn’t have existed before the nineteenth century, when Latin American nations formed after independence from Spain. Of course, what it meant to be Mexican American, Cuban American, Puerto Rican, and so forth, was always informed by the coming together of European, Indigenous, and African peoples, and the social and racial hierarchies that both defined and circumscribed their relationships with one another. This understanding of national identity consolidated in the early twentieth century, when multiple Latin American nations articulated some sense of racial mixture between Europeans, Indigenous peoples, and Africans as the core of what it meant to be citizens of individual nations, and Latin American more generally—even though African roots were downplayed or denied, and even though Indigenous belonging hinged on assimilation.

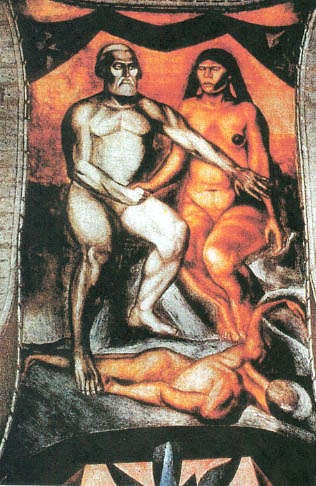

Probably the most famous articulation of race mixture as the defining characteristic of national identity came from José Vasconcelos, Mexico’s Secretary of Public Education in the decade after the Mexican Revolution, when it was important to come forge national unity after a decade of civil war. Published in 1925, his essay “La Raza Cosmica”—the Cosmic Race— argued that the four races of the world (“the Black, the Indian, the Mongol, and the White”) would fuse to form a fifth race that would be superior to all other races that came before. The supposedly science-based white supremacy that had defined an earlier era of human history was temporary, and would give way to something better. Vasconcelos commissioned the artist José Clemente Orozco to paint a mural at the old Colegio de San Ildefonso that allegorized the birth of the Mexican race. It depicted the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortes and the Nahuatl-speaking Indigenous woman, Malintzin, or La Malinche. The pale Cortes seems to be restraining Malintzin, and has his foot placed firmly on the back of a dead Indigenous man. Cortes and Malintzin had a child together, Martin Cortes, whose birth symbolized the birth of the mestizo race. Mexican Americans have seen the union between Cortes and Malintzin as their own origin story as well. This is where Townsend’s book about the Aztecs comes in.

Many Mexican Americans and Latinos to this day tell clear and unambiguous tales about mesoamerica and the Spanish conquest. They’ve told different tales, to be sure, but not many of them are particularly nuanced or complex. For many, the conquest is a story about the erasure of Indigenous cultures and communities. For some, the conquest meant the introduction of Spanish civilization, and the moment to which they trace their family’s lineage in the Americas. For many Latinos, the Spanish colonial period is something to either be condemned or celebrated. I want to be clear when I say that there is no such thing as good conquest, but I also think that the stories we tell about Spanish colonialism should start from a place of trying to understand the world as the actors living in it experienced it, instead of projecting back onto them our own values and expectations. Camilla Townsend does this beautifully, with important lessons for Mexican Americans today. I’ll mention three examples.

When Chicanos in the 1960s and 1970s created their own origin story, they started referring to Aztlán as the mythical Chicano homeland, because what is today the American Southwest had been the ancestral homeland of the Aztecs before they made their centuries-long trek to Mexico’s central valley. They also embraced some elements of Vasconcelos’s cosmic race, because they saw themselves as the the descendants of Spaniards and Indigenous people. (In doing so, they erased the African heritage that was also part of Mexican identity—just see Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzalez’s epic poem, “I Am Joaquín”). But unlike Vasconcelos, they emphasized their Indigenous roots above their Spanish roots, as a form of cultural reclamation; to repair the damage done by the conquest. Mexican Americans weren’t alone in doing this. Puerto Rican activists at the same time, for example, led a Taíno revival that emphasized the Indigenous roots of the Caribbean. But in emphasizing their indigeneity, they told oversimplified tales of Indigenous identity and resistance against Spain. Townsend complicates the story considerably. She notes that the name “Aztec” is itself made up. There was no such thing, either before or after contact with Spaniards, as a single group called the Aztecs, who, in fact, were a mixture of Indigenous peoples from throughout central Mexico.

Chicanos in the 1960s and 1970s also revived the story of Cortes and Malintzin’s union, and began calling Malintzin a traitor to her people because she became a translator and intermediary between Spaniards and Indigenous people, and therefore helped facilitate the conquest. She was a captive who had been sold into slavery as a child, and didn’t have any particular allegiance to Moctezuma and his subjects. As Townsend notes, because Malintizin had been taken captive by one group and sold to another, she knew that not all Indigenous people were “all on the same side,” so she would never have thought that she was betraying her own people. I’m not sure whether the Latinos today who celebrate their Indigenous ancestry are celebrating ancestors who may have been power-hungry enslavers. I doubt it very much. Malintzin wasn’t a hero to be celebrated as the mother of the Mexican race, which is how some have seen her. But neither was she a traitor to be vilified. Instead, she was a person trying to survive and navigate a new difficult reality, and she did so, Townsend argues, as best she could.

In the final two chapters of her book, Townsend writes about the decades after the conquest, and how the Indigenous peoples who survived it began to think and write about what they had endured. Indeed, one of the most amazing aspects of the work she did was to carefully read the annals of the conquest written by Nahuatl-speaking Indigenous people, in addition to the accounts written by Spaniards that formed the crux of what other scholars have relied on in order to write its history. What she finds is destruction and trauma, for sure, but also survival, an attempt to make sense of what had happened, and an effort to move forward—not beyond, but forward. Like historians of other Indigenous communities in the Americas, therefore, Townsend tries to narrate the conquest as something other than an ending point. It was a critical turning point and one that caused immeasurable harm and pain that Mexicans and Mexican Americans continue to reckon with, but it was not the end of the story. She notes that there are some 1.5 million Nahuatl speakers today.

To me, the main takeaways from these three examples are: Mexican Americans in the recent past have told stories about their Indigenous roots largely to meet their needs in the present, rather than as part of an effort to understand the complex histories of Indigenous communities in the past; we’ve told oversimplified tales of what it meant to be Indigenous at the time of the conquest, in part due to efforts in the early twentieth century to incorporate a singular understanding of indigeneity into the definition of mestizaje, which was seen as the crux of Latin American and Latino identity; and that histories of survival and adaptation should be told alongside histories of the wreckage of conquest. Emphasizing our indigeneity has been an important way for Latinos to resist ongoing colonialism, and to express our solidarity with other marginalized communities. But Townsend implies—to me, at least—that if we wish to continue seeing Indigenous peoples at the time of the conquest as our distant ancestors, we should write histories about them that aim to be as complex as the realities they lived through.

Because the midterm elections are five days away, perhaps you expected something about Latino politics. Sorry to disappoint! If you need your fix, check out this post by Ruy Teixeira, “Hispanic Voters on the Eve of the 2022 Election,” or one of the hundreds of other news stories about Latino voters published recently. I will scratch your Latino politics itch on Monday, the day before the midterms.

I recently read the new book “Conquistadores” by Fernando Cervantes, which attempts to explain the conquest via the mindset of medieval Europe. This book seems like a perfect pairing, and I’ll definitely read it next. I live in CDMX and have written about how the wave of recent immigration of remote workers is often framed within the conqueror/conquered binary - in a way I feel is quite limiting and fails to capture the complexity of globalization. Perhaps reading this book will give me more context for the present moment. Thank you for sharing.

I happened to read Dr. Townsend's book before it won the Cundhill (it was nice to have a rooting interest as they whittled down the list). Thought it was a fantastic read. Hard to believe the Nahuatl texts were sitting there the whole time and so few others were utilizing them!